Hey so it’s the Melbourne International Film Festival for the next couple of weeks and hooray they have lots of lady-directed films on, so much so that I can’t actually afford to see them all but I am going to at least make it along to a few.

And this is the first one.

So, Nan Goldin is kind of a legend. Her phenomenal pictures capture a beautiful dark side of human nature, and for me it feels like when you look at her photos, you see something that we all know is there but rarely express to one another: that deeply buried tragedy, pragmatism, joy, pride and general neediness of the human condition.

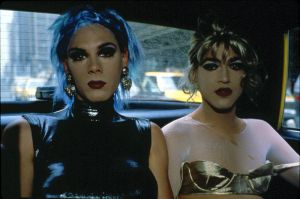

Her photo-slideshows, especially her constantly updated and re-imagined seminal work The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, simultaneously give the sense of capturing an important time and a place in history (Berlin squats, New York in the epicentre of the 1980s AIDS epidemic, a burgeoning LGTBQ and arts culture) while also projecting a sense of transience and immediacy, they are snapshots and polaroids snuck in drunken moments at parties, lonely journeys on trains and in the backs of taxis.

Her photo-slideshows, especially her constantly updated and re-imagined seminal work The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, simultaneously give the sense of capturing an important time and a place in history (Berlin squats, New York in the epicentre of the 1980s AIDS epidemic, a burgeoning LGTBQ and arts culture) while also projecting a sense of transience and immediacy, they are snapshots and polaroids snuck in drunken moments at parties, lonely journeys on trains and in the backs of taxis.

Nan Goldin: I Remember Your Face is a meandering, slice of life documentary, directed by Sabine Lidl. With charming simplicity it carefully captures Nan’s curious nature, her close friendships which have inspired her photo subjects and that constant tension between living life as an artist and the realities of the mundane like how the bills get paid and how it feels to always fall in love with gay men.

Nan Goldin: I Remember Your Face is a meandering, slice of life documentary, directed by Sabine Lidl. With charming simplicity it carefully captures Nan’s curious nature, her close friendships which have inspired her photo subjects and that constant tension between living life as an artist and the realities of the mundane like how the bills get paid and how it feels to always fall in love with gay men.

However, on the other side of the scale this film felt very haphazard – intensely personal subjects like childhood trauma, self mutilation and drug addiction get a quick once over but are never delved into, we jump from place to place without reason or explanation and the film feels a wee bit as if it is trailing behind Nan just trying to keep up.

The camerawork is hand-held and extremely low fi, and, while in some ways this does mirror Nan’s snapshot aesthetics, when you take a good look at her slideshows and collections, Nan’s work also feels carefully curated. It would have been nice to see some more constructed shots that reflect the curatorial side of Nan’s artwork as well.

For me, what makes Nan’s art important and interesting is that vulnerable darkness she seems to pull out of her subjects using just light and a camera, something that this documentary never quite seems to pull out of her, although it gets tantalisingly close a few times.

In short, the documentary is lovely, and if you’re a fan of Nan Goldin it’s decidedly worth seeing, but the most enjoyable parts are when the camera stops moving, Nan stops talking and we just dwell on her glorious photographs for a time. Which I am going to do now: